Died March 16

AD 37, Capreae [Capri], near Naples

in full Tiberius Caesar Augustus or Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus , original name Tiberius Claudius Nero second Roman emperor (

AD 14–37), adopted son of

Augustus, whose imperial institutions and imperial boundaries he sought to preserve. In his last years he became a tyrannical recluse, inflicting a reign of terror against the major personages of Rome.

Background and youth

Tiberius's father, also named Tiberius Claudius Nero, a high priest and magistrate, was a former fleet captain for Julius Caesar. His mother, the beautiful Livia Drusilla, was her husband's cousin and may have been only 13 years old when Tiberius was born. In the civil wars following the assassination of Julius Caesar, the elder Tiberius gave his allegiance to Mark Antony, Caesar's protégé. When Augustus, Caesar's grandnephew and heir, fell out with Antony and defeated him in the ensuing power struggle, the elder Tiberius and his family became fugitives. They fled first to Sicily and then to Greece, but by the time Tiberius was three years old an amnesty was granted and the family was able to return to Rome.

In 39 BC Augustus had the power, if not yet the title, of emperor. Attracted by the beauty of Livia, who was at that time pregnant with a second son, Augustus divorced his own wife, who was also pregnant, and, forcing the elder Tiberius to give up Livia, married her. The infant Tiberius remained with his father, and, when the younger brother, Drusus, was born a few months later, he was sent to join them. At the death of his father, Tiberius was nine years old, and, with Drusus, he went to live with Livia and the emperor. The two boys and the emperor's daughter, Julia, between them in age, studied together, played together, and took part in the obligatory ceremonials of temple dedication and celebration of victories. They were joined by their cousin Marcellus, the son of Augustus's sister, Octavia.

In the absence of a clear law designating Augustus's successor as emperor, all three boys were trained accordingly. They were instructed in rhetoric, literature, diplomacy, and military skills, and soon they also began taking a ceremonial role in the affairs of state. As oldest, Tiberius was the first to do so. In the triumph following Augustus's victory over Cleopatra and Antony at Actium, the 13-year-old Tiberius rode the right-hand horse of Augustus's chariot in the procession. Though not a striking figure, he conducted himself well.

Serious by nature, he had become a shy youth, though he was sometimes called sullen. His great talent was application. With the best teachers in the empire at his disposal and, above all, as a participant in life at the palace, the centre of the civilized Western world, he learned rapidly. By age 14, Tiberius was used to dining with kings of the empire, to conducting religious services over the heads of powerful men five times his age, and even to seeing his own form in marble statues.

Years in the shadow of Augustus

Tiberius was not handsome. As a teenager he was tall and broad-shouldered, but his complexion was bad. His nose had a pronounced hook, but that was typically Roman. His manner was disconcerting. He had a slow, methodical way of speaking that seemed intended to conceal his meaning rather than make it plain. But he was diligent. He may not have known he would be emperor, but he cannot have doubted that he would be at least a general at a rather early age and thereafter he would be a high official in the government of Rome. In 27 BC, when Tiberius was 15 years old, Augustus took him and Marcellus to Gaul to inspect outposts. They experienced no fighting, but they learned a great deal about how to rule the marches, keep fortifications intact, and keep garrisons alert. When they returned, Augustus gave Marcellus his daughter Julia as wife.

Then Tiberius himself married. Love matches were infrequent in imperial Rome, but Tiberius's marriage to Vipsania Agrippina was one. She was the daughter of Marcus Agrippa, Augustus's son-in-law and lieutenant. Besides his love for his wife, and for his brother, Drusus, now growing into manhood, he was occupied with important work. His first military command at age 22, resulting in the recovery of standards of some Roman legions that had been lost decades before in Parthia, brought him great acclaim. As a reward he asked for another active command and was given the assignment of pacifying the province of Pannonia on the Adriatic Sea. Tiberius not only conquered the enemy but so distinguished himself by his care for his men that he found himself popular and even loved. When he returned to Rome, he was awarded a triumph.

Tiberius's happy years were coming to an end, however. His beloved brother, Drusus, broke his leg in falling from a horse while campaigning in Germany. Tiberius was at Ticinum, on the Po River, south of what is now Milan, 400 miles away. Riding day and night to be with his brother, he arrived just in time to see Drusus die. Tiberius escorted the body back to Rome, walking in front of it on foot all the way. He also had to give up his wife, Vipsania, the other person he loved. Augustus's daughter Julia had become a widow for the second time. Her first husband, Marcellus, had died, and the emperor had married her to Agrippa (who, as Vipsania's father, was Tiberius's father-in-law). When Agrippa died in 12 BC, Augustus wanted her suitably married at once and chose Tiberius as her third husband. Tiberius had no more choice than his father had had when Augustus decided to marry Livia. Tiberius was as obedient as his father. He divorced Vipsania and married Julia.

Tiberius's new wife has come down in history with a reputation for licentiousness. It is not certain how much of the reputation she deserved. Roman historians often dealt in gossip, inventing scandal when there was none; but in Julia's case they had good reason for their opinion. When Julia married Tiberius, he was 30. She was 27, twice a widow, the mother of five children (not all surviving). She was pretty and light-minded and liked the society of men. She did not get along with her mother-in-law (who was also her stepmother), Livia, and after the first few months she tired of Tiberius. It is certain that she committed adultery, and this presented Tiberius with an immense problem, not only personal but also political. A law of Augustus himself required a husband to denounce a wife who committed adultery. But Julia was the emperor's beloved child, and, as Augustus knew nothing of her vices, to denounce her would be to wound him, and that was dangerous.

With no good course of action to follow, Tiberius asked for and received fighting commands away from Rome. When once in Rome between battles, he chanced to see Vipsania at the home of a friend. She had, at Augustus's orders, been remarried to a senator. Tiberius was so overcome with sorrow that he followed her through the streets, weeping. Augustus heard of it and ordered Tiberius never to see her again. Although Augustus heaped honours on Tiberius, they did not compensate for Julia's behaviour. In 6 BC Tiberius was granted the powers of a tribune and shortly thereafter went into a self-imposed exile on the island of Rhodes, leaving Julia in Rome.

Tiberius was now 36 years old and at the pinnacle of his power. He was capable of ruling an empire, conducting a great war, or governing a province of barbarians. In Rhodes he had nothing to do, and all of his ability and strength appear to have turned inward, into strange and unpleasant behaviour. Although the histories of Tiberius's reign—written either by flatterers, like his old war comrade Velleius Paterculus, or by enemies—are not wholly trustworthy, there can be no question that a change took place in Tiberius at this time. What emerged was a man who seemed interested only in his own satisfactions and the increasingly perverse ways to find them. On Rhodes Tiberius became a recluse—unassuming and amiable at first, resentful and angry later on. Though Tiberius had left Rome of his own free will, daring the emperor's wrath, he could not return without Augustus's permission. Augustus withheld that permission for the better part of a decade.

Eventually, Livia secured proofs of Julia's many adulteries and took them to Augustus, who was furious. Under his own law she should have been executed, but he did not have the heart for that; instead, he exiled her for life to the tiny island of Pandateria. But even then Tiberius was not recalled. There were three young men whom the emperor appeared to favour as heirs, all sons of Julia. One of them, Postumus, reportedly no more than a boor, fell into disfavour with Augustus and was sent into exile with his mother. The other two, Lucius and Gaius, were clearly candidates to succeed. But in 2 BC Lucius died in Massilia (Marseille), and the emperor relented. He called Tiberius back to Rome. By AD 4 Tiberius was in possession of all his honours again, and in that year Gaius was killed in a war in Lycia. Tiberius had become the second man in Rome. Augustus did not like him, but he adopted him as his son. He had no choice, and he was growing old. Tiberius was the least objectionable successor left.

Tiberius became proud and powerful. His statues had been torn down and defaced while he was in Rhodes. Now they were rebuilt. He was given command of an army to quell Arminius, who had destroyed three Roman legions in Germany in AD 9; he succeeded wholly. He was succeeding at everything now, and in AD 14, on August 19, Augustus died. Tiberius, now supreme, played politics with the Senate and did not allow it to name him emperor for almost a month, but on September 17 he succeeded to the principate. He was 54 years old.

Reign as emperor

Although the opening years of Tiberius's reign seem almost a model of wise and temperate rule, they were not without displays of force and violence, of a kind calculated to secure his power. The one remaining possible contender for the throne, Postumus, was murdered, probably at Tiberius's orders. The only real threat to his power, the Roman Senate, was intimidated by the concentration of the Praetorian Guard, normally dispersed all over Italy, within marching distance of Rome.

Apart from acts such as these, Tiberius's laws and policies were both patient and far-seeing. He did not attempt great new conquests. He did not move armies about or change governors of provinces without reason. He stopped the waste of the imperial treasury, so that when he died he left behind 20 times the wealth he had inherited, and the power of Rome was never more secure. He strengthened the Roman navy. He abandoned the practice of providing gladiatorial games. He forbade some of the more outlandish forms of respect to his office, such as naming a month of the calendar after him, as had been done for Julius Caesar and Augustus.

There were, to be sure, occasional wars and acts of savage repression. Tiberius's legions put down a provincial rebellion with considerable bloodshed. In Rome itself, on the pretext that four Jews had conspired to steal a woman's treasure, Tiberius exiled the entire Jewish community. The most ominous and least defensible aspect of Tiberius's first years as emperor was the growth of the practice called “delation.” Most crimes committed by well-to-do citizens were, under Roman law, punished in part by heavy fines and confiscations. These fines contributed in large part to the growth of the imperial treasury, but the money did not all go to the fiscus. Because there were no paid prosecutors, any citizen could act as a volunteer prosecutor, and, if the person he accused was convicted, he could collect a share of the confiscated property. These volunteers, called delatores, made a profitable career of seeking out or inventing crime. Many of the prosecutions were based on rumour or falsified evidence, and there were few Romans who were so honoured or so powerful that they did not need to fear the attack of the delatores on any suspicion, or on none at all.

In AD 23 Tiberius's son Drusus died. He had not been particularly loved by his father, but his death saddened Tiberius. From then on he spared less and less thought to the work of empire. More and more he delegated his authority in the actual running of affairs over to the man he had entrusted with the important command of the Praetorian Guard, Sejanus. Before long Tiberius was emperor only in name.

Ironically, the death of Drusus, the event that brought Sejanus to power, may have been Sejanus's own doing. Apparently Sejanus had seduced the wife of the younger Drusus, Livilla, and induced her to become his accomplice in murdering her husband. The evidence is not absolute and has been questioned by many historians, but it was not questioned by Tiberius. In AD 27, at age 67, Tiberius left Rome to visit some of the southern parts of Italy. En route he paused to go to the island of Capri. His intention appears to have been only to stay for a time, but he never returned to Rome. It is the remaining decade or so of Tiberius's life that has given rise to the legend of Tiberius the monster. It seems probable, to begin with, that Tiberius, never handsome, had become repulsively ugly. First his skin broke out in blotches, and then his complexion became covered with pus-filled eruptions, exuding a bad smell and causing a good deal of pain. He built himself a dozen villas ringing Capri, with prisons, underground dungeons, torture chambers, and places of execution. He filled his villas with treasure and art objects of every kind and with the enormous retinue appropriate to a Caesar: servants, guards, entertainers, philosophers, astrologers, musicians, and seekers after favour. If the near-contemporary historians are to be believed, his favourite entertainments were cruel and obscene. Even under the most favourable interpretation, he killed ferociously and almost at random. It is probable that by then his mind was disordered.

Tiberius had not, however, lost touch with the real world. He came to realize just how strong he had made Sejanus and how weak he had left himself. In AD 31 he allowed himself to be elected consul of Rome for a fifth time and chose Sejanus as his co-consul. He gave Sejanus permission to marry Livilla, the widow of Tiberius's son. Now Sejanus not only had the substance of power but its forms as well. Golden statues were erected to him, and his birthday was declared a holiday. But Tiberius had come to fear and mistrust him. With the aid of Macro, Sejanus's successor as commander of the Praetorians, Tiberius smuggled a letter to the Senate denouncing Sejanus and calling for his execution. The Senate was shocked and taken aback by the swift change, but it complied instantly—perhaps moved by the justice of Tiberius's charges or by the strength of the Praetorian Guard.

Apparently Tiberius now reached a peak of denunciation and torture and execution that lasted for the remaining six years of his life. In the course of this reign of terror his delatores and torturers found evidence for him of the murder of his son, Drusus, by Livilla and Sejanus. Many great Roman names were implicated, falsely or not, and while that inquisition lasted no one on Capri was safe. Tiberius's chief remaining concern for the empire was who would rule it when he was gone. There were few living successors with any real claim, and Tiberius settled, as Augustus had done before him, on the least offensive of an undesirable lot. His choice was Gaius Caesar, still a young boy and known by the nickname the Roman legions had given him when he was a camp mascot, Caligula, or Little Boots. Caligula, a great-grandson of Augustus through Julia and her daughter, had a claim to the throne as good as any. If his morals and habits were less than attractive, Tiberius did not seem to mind. “I am nursing a viper in Rome's bosom,” Tiberius observed, and named Caligula his adopted son and successor.

In the spring of AD 37, Tiberius took part in a ceremonial game that required him to throw a javelin. He wrenched his shoulder, took to his bed, became ill, and lapsed into a coma. His physicians, who had not been allowed to examine him for nearly half a century, now studied his emaciated body and declared that he would die within the day. The successor, Caligula, was sent for. The Praetorian Guard declared their support for the new emperor. The news of the succession was proclaimed to the world. Then Tiberius recovered consciousness, sat up, and asked for something to eat. The notables of Rome were thrown into confusion. Only the Praetorian commander, Macro, kept his head, and on the next day he hurried to Tiberius's bed, caught up a heap of blankets, and smothered Tiberius with them.

Assessment

As an infant Tiberius had been a fugitive and then a pawn. As a man he had been a popular and victorious general and then an exile. He came to supreme power already growing old. When he died, he left the Roman Empire prosperous and stable, and the institution of the principate was so strong that for a long time it was able to survive the excesses of his successors. Without him the later history of Rome might have been less colourful, but probably it would also have been far shorter.

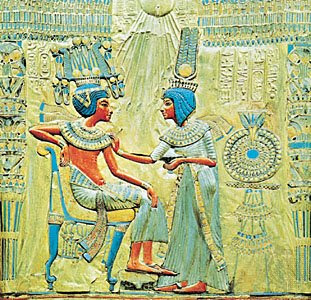

King Tutankhamen and Queen Ankhesenamen, detail from the back of the throne of Tutankhamen; in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

King Tutankhamen and Queen Ankhesenamen, detail from the back of the throne of Tutankhamen; in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

Tutankhamen, gold funerary mask found in the king's tomb, 14th century BC; in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

Tutankhamen, gold funerary mask found in the king's tomb, 14th century BC; in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo.